Turkish botanist, Levent Can came to study specimens in our herbaria within the SYNTHESYS project. He is writing his Ph.D. dissertation at the University of Istanbul and also working as a research assistant at the Namik Kemal University in Tekirdağ (Turkish city on the northern coast of Marmara Sea). In 2013, he won a prestigious scholarship from DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service), which gave him an opportunity to do following research for his PhD studies at the Carl von Ossietzky University – Oldenburg. Levent arrived at the Hungarian Natural History Museum from Germany accompanied by his wife, Seda.

Tell us more about the crocuses. Why did you choose these plants as your research topic?

My supervisor, who had been working on crocuses for many years, advised me to study these plants, because a lot of unanswered questions and confusing issues still occur regarding their relations and chromosome numbers.

I basically research the wild species of Crocuses. They are related to the saffron plant, which is generally known as an exotic spice. These plants are so called geophytes. It means they have bulbs in the ground, which contain starch. The starch helps them to survive the hot and very dry summer of the Mediterranean area where these plants are distributed. For my PHD thesis, I study a particular group of species, namely the Flavi group. They bloom in spring and most of them grow yellow flowers. I study their systematics, evolutionary history and phylogenetic relationships. I try to answer questions such as “Which plants are more related with each other” or “Which plants of these groups are more basal (old or primitive)”. I collect the plants mostly in Turkey but I do the molecular studies in modern laboratories of the Carl von Ossietzky University in Germany.

Crocus biflorus from southern Turkey (photo: Levent Can)

How did you get in contact with the Hungarian researchers?

It was a year ago when the Synthesys project was opened for application. The aim was to visit a herbarium which has a significant collection from the Carpathian and the Balkan areas. As I knew making collecting trips and doing research of these areas have tradition in Middle- Europe, Budapest or Vienna seemed to be the best choice. First, I contacted Vienna but I was informed that they did not have crocuses since the collection had been destroyed during The Second World War. They advised me to try the Hungarian Natural History Museum (HNHM), so I contacted Dr. Zoltán Barina, the curator of the Herbarium Carpato- Pannonicum. He confirmed the museum holds a significant crocus collection from the Carpathians and the Balkans. After I had got the good news, I immediately applied for the Synthesys project. I have to tell, the richness of the Botanical Department was awe-inspiring and working in the collection, which holds ca. 1400 historically significant specimens, was like heaven for me.

What are the main objectives of this SYNTHESYS project?

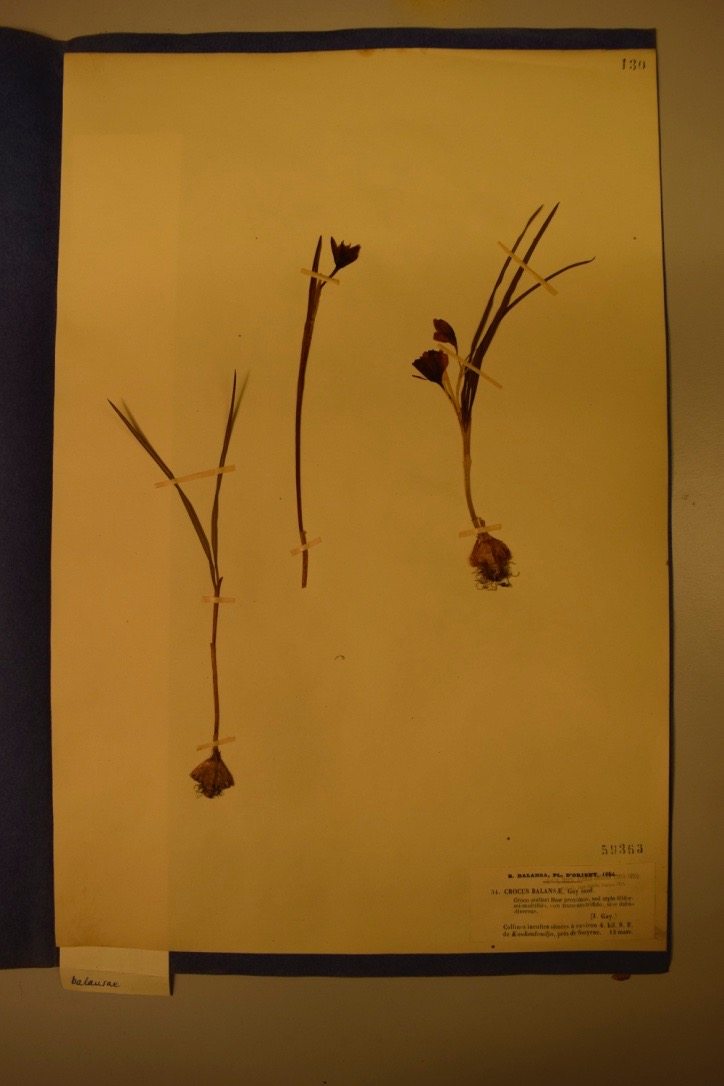

On my field, it is very important to have an idea about the distribution of the examined species. The most essential way for botanical studies is to visit herbaria, where you can find species from different localities. It is particularly true in the case of crocuses, as their exploration is very difficult due to the topographical conditions and their short flowering period. In this historical Herbarium, you can find specimens from the Balkans collected in the last 150 years, which provide a good base for a comprehensive analysis of their distribution. For example, you can compare specimens collected from Romania with Croatian ones. Another important aim of my research is to reveal phylogenetic relations. For precise results of the evolutionary processes, I have to focus on the geographical distribution of the species. Another important question is the examination of variations within the species. I think the following example could demonstrate this question. I find a particular species in Anatolia while the same species can also be found in the Hungarian samples that were collected in Croatia. The different distribution could cause morphological variations such as the color of the flower. The Turkish crocus has purple stripes while the Croatian one does not have that pattern. Without studying different specimens of the same species in herbaria we could easily make the mistake to describe the Turkish species as new to science. I could not emphasise enough the importance of visiting Herbaria.

Crocus biflorus from Southern Turkey Photo: Levent Can

Can you name famous researchers of this collection?

Actually, this collection is international, which has been enriched by different researchers from different countries. Studying these samples feels like holding precious archeological findings in your hands. In 1886, an English researcher, George Maw wrote a monograph about crocuses. He could be considered as the father of crocus research. About 150 years ago he was here in this Herbarium. He took notes, wrote comments of these specimens, and also made corrections. I felt privileged when I read the original notes of these outstanding researchers.

Crocus balansae collected in 1854 from western Turkey.

Photo: Levent Can

Tell us more about your collecting expeditions.

I collect mainly in West Anatolia, Turkey. I also visit the Taurus Mountains in South Anatolia either with my supervisor or my wife every year. The high mountain ranges, parallel to the Mediterranean Sea, are very important for the flora and fauna. Because of the diversity, there is a good chance that we find new species, plants, or populations.

In 2014, I went to Israel near the Golan Heights and the lake Galilee to collect a particular plant, the Crocus hyemalis. Now I am planning to go to the Balkans next year using the knowledge I obtained in the HNHM. I will make my database of the collected plants, including the names of the collectors and the localities.

Are you planning to go together with the Hungarian researchers?

I will ask Dr. Zoltán Barina to join me with his team or recommend someone for this trip who is an expert of crocuses or geophytes.

Do you have an interesting story about collecting trips?

Certainly! (He laughs). The problem with collecting geophytes such as crocuses is that you can only find them during their flowering term. That is why we make our trips mostly in February or March. You can imagine the circumstances in the high mountains where you have to hike in that period of the year. We usually rent a car and we have incidents with it every year. Two years ago, we had a four- wheeler off-road car. We were heading to the top of the Taurus Mountains, when the car accidentally slipped on the wet Terra Rossa soil, which was like ice. The tyres were sliding downwards on the slope and after a few meters at the edge of a trench, the car struggled in a pitch. Fortunately it was well equipped, so we fixed the vehicle to a big rock with a metal rope, and with the help of a motorized winch, we managed to save it from sagging. The expedition was a total failure; we lost three or four hours in the mountains without finding the plant. We were fairly frustrated. Down in the city, we spent hours cleaning up and checking the car. Without any exaggeration, I could say we get in some kind of trouble every time we are in field. However, after a few days, we cannot wait to collect again.

Which is your favourite species?

Last year, my wife and I went on a trip to the famous Mount Spil (to the city of Manisa near Izmir,) in West Turkey. We climbed up to 1000 meters with the hope of finding a few saffrons. Unfortunately, we found nothing but our footprints since the mountain was covered with thick snow. This year the weather was good, so we tried again, and finally found that species. It was a big surprise for us. The plant was so glamorous, that it was worth waiting a whole year. It has yellow flower with wine red stripes on the back. So far, this is my favourite species.

Crocus olivierisubs. balansae, Levent Can’s favourite species from the Mount Spil (Photo: Levent Can)

How can you protect these plants from deforestation or agricultural cultivation?

These geophytes are particularly threatened in their natural habitats. In Turkey, orchids are used to make a hot drink called salep. In rural areas, inhabitants simply pull the bulbs out of the ground and grind them. Then they boil that with milk and some spices (for example cinnamon), and make a hot drink of that. The uncontrolled collecting activities around the villages mean a serious threat to the orchids and other geophyte populations.

What is the situation near cities?

It may sound surprising but there is a species that is endemic to Istanbul. This actually means that the only locality of that saffron is in our capital. Istanbul is an enormous city with a population of 14 million residents and it is constantly growing. Until now the endemic saffron plant has been protected by a forestry border at least a little, but it seems to be destroyed in the near future by construction work of a third bridge above the Bosporus. You are helpless in such a situation, because we need this bridge to reduce the huge traffic indeed.

What could be the solution in this case?

We have this species cultivated in botanical gardens. If something happened to the natural habitat, we could reconstruct them with the help of some samples and genetic material. Obviously, we cannot guarantee that these plants will grow and reproduce in a different locality as effectively as in their original habitat. They would probably be mixed with other geophytes or could be harmful for the natural habitat of other species. Protection is a complicated question.

All of these crocus species are protected?

Actually, not all of them. There is a list of protected and endangered species (IUCN), which defines it. If you want to have a plant protected, you have to research your chosen plant and populations and fill an application form of IUCN. Most of the crocuses are not in this list yet, but it is my aim to make at least some of them protected.

Which other Synthesys partner institutions would you like to visit?

I think the French National Museum of Natural History in Paris, which holds a lot of interesting historical collections, or the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. The book The Flora of Turkey was written there in the sixties by an English botanist and his collection is also preserved there.

Did you enjoy your stay in Budapest? Were you satisfied with the conditions here?

Budapest was actually a pleasant surprise for us. We had not expected it to be so nice, and the public transportation is excellent. We enjoyed sightseeing, visiting several monuments and of course, a lot of museums. The Hungarian Parliament Building was especially captivating for me. If there was another list of Seven Wonders of the World, this impressive building should be one of them. We also made a trip to the Margaret Island by public boat. Both sides of the city were spectacular from there. And of all the culinary delights, the goulash was really special and tasty. We are leaving Budapest with a warm heart.

Would you return?

That would be wonderful if we could try the spa culture here in winter. Unfortunately, the Turkish bath tradition has been fading away at home but I am glad to see it is still alive here.

Written by Bernadett Döme, Krisztián Kucska

Photos by Szabolcs Simó