Georgios Georgalis is a PHD candidate in palaeontology at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland.

The Greek researcher studies fossil finds of reptiles particularly from the Aegean region (Greece and the western part of Turkey). Georgios has a rather diverse topic since he does comparative analysis of recent and extinct specimens which belong to three large reptile groups: lizards, snakes and turtles. Before his stay at the Hungarian Natural History Museum within the Synthesys program, Georgios also visited the Herpetological Collections of the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Madrid and the Natural History Museum in Vienna to examine skeletons of extant snakes.

What is the main objective of your Synthesys project?

The aim of my Synthesys project is to describe the vertebral anatomy of all European snakes that live today on our continent. My purpose is to apply this knowledge to fossil specimens found in Europe and to determine how they were related to the extant fauna.

Why was our institution attractive in this aspect?

I contacted the curator of Herpetology, Judit Vörös, to ask her about available material of extant snakes. Soon she sent me a long list of snake specimens and one taxon, the Hungarian meadow viper (Viperaursiniirakosiensis), which is exclusively endemic to Hungary and Transylvania, really grabbed my attention. As gaining knowledge about it was essential for my research, I could not wait to come here. I can tell I did not get disappointed when I realised the excellence of this comparative material.

Do you study recent reptiles as well?

I mostly study fossil reptiles but I need to be extensively familiar with the anatomy of lizards, snakes and turtles. Therefore, I also examine the skeletons of recent species to be able to apply this knowledge to the fossil record of snakes, which were much more abundant and diverse once in Europe than today.

Which is the favourite part of your job?

It is rather my passion than a simple job. I am passionate about the research of extinct reptiles, especially when I discover something new.

Have you managed to discover new species?

Yes, I have actually managed to describe a new species of turtle, which was named Nostimochelone lampra. This species was a so- called side-necked (Pleurodira) turtle. The peculiarity of the finding is that the side-necked turtles group is only inhabiting the Southern hemisphere today, and became extinct from the European continent a long time ago, however, the fossil of Nostimochelone lampra was found in an 18 million year old sediment in western Greece.

Figure: Photograph of the only fossil of Nostimochelone lampra. (Photo: Georgios Georgalis)

Why is it called side-necked turtle?

This is a category or a group of turtles that refers to the retraction of the neck into their shell. Today in Europe, all turtles belong to the hidden-necked (Cryptodira) group.

Where do you usually go on collecting trips?

Most of the material I study was discovered in the base of excavations that actually aimed for the big fossil mammals. The majority of the palaeontologists, particularly the previous generation, focused on large mammals and the reptiles were sometimes found adventitiously. Consequently, most reptile fossils remained unstudied for decades. Now I have been visiting collections for the purpose of describing these neglected specimens. In addition, I also participate in excavations around Thessaloniki, in collaboration with the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Could you describe your most interesting find?

My favourite discovery was a fossil of the 4 million year old giant viper, (Laophiscrotaloides) which was excavated near the city of Thessaloniki. This enormous creature was probably the biggest viper of all time. It had been discovered previously and for the first time by the world famous palaeontologist Richard Owen in the 19thcentury. His material unfortunately got lost and there was not any trace of this mysterious giant viper for a long time. The rediscovery of the new finding from the same locality proves that the giant viper really existed. The new vertebra provides valuable information about the taxonomic status and size of this bizarre, enigmatic snake.

This new finding was described in the following paper:

Georgalis, G.L.,Szyndlar, Z., Kear, B.P. and Delfino, M. 2016. New material of Laophiscrotaloides, an enigmatic giant snake from Greece, with an overview of the largest fossil European vipers. Swiss Journal of Geosciences 109:103–116.

The vertebra of the giant viper Laophiscrotaloides. (Photo: GeorgiosGeorgalis)

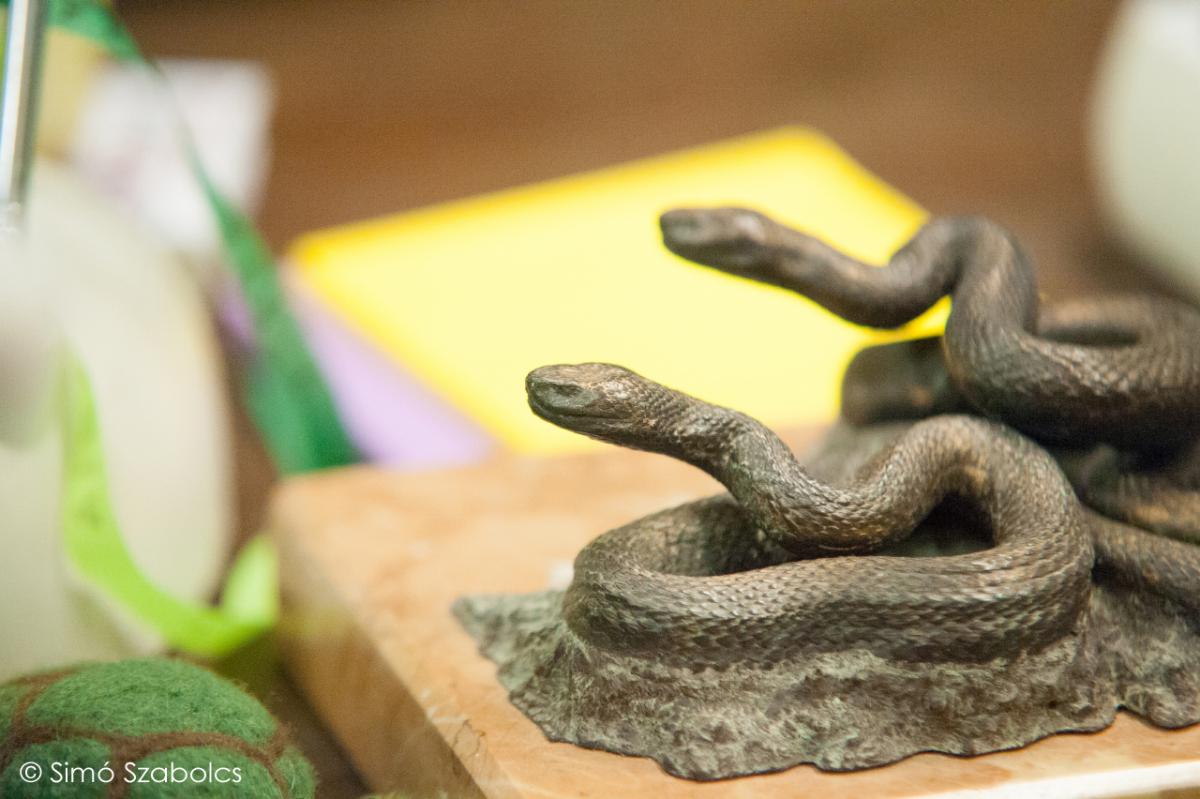

Can you show us some skeletons from the collection?

Here is a big boa (Boa constrictor) for example. Generally we store the material disarticulated. It means that the vertebrae and the ribs are scattered. The vertebrae, situated in the mid trunk region, are the biggest, so these are the most commonly found elements for paleontological analysis.

How long do you think it could have been?

Snakes generally have numerous vertebrae and the ribs can extend a lot. As this snake was a boa, it must have been thick. It is almost impossible to determine the length precisely; however, mathematical models can help us to estimate. It could have been approximately 3 meters long.

How many vertebrae does a snake have?

It may sound funny but many people think that snakes do not have bones at all. It depends on the species, but in some already known fossil species, the number of the vertebrae was more than 350. That is quite a lot. Every vertebra has distinctive features. It is characteristic that the vertebrae connect with each other in a perfect way. This happens because the cotyle and the zygosphene (anterior parts) of one vertebra unite perfectly and lock with the condyle and the zygantrum (posterior parts) respectively of the previous vertebra in the row. This way, the spinal column can be very flexible, so the snake can move rapidly and attack suddenly.

Does the Herpetological Collection hold full snake skeletons?

We only have that for exhibition at the Ludovika storage room, adds Judit Vörös. For scientific examinations, full snake skeletons are mostly useless, since the bones are attached and glued together. We have to examine the disarticulated specimens one by one. However, every time I look at a full long snake skeleton I am amazed.

Do you study skins as well?

Unfortunately, skins cannot be preserved during millions of years. However, sometimes outstanding fossil snakes are found. Around France, in particular localities in the Quercy region, there have been mummified snake skins found that are more than 40 million years old. The Baltic amber also preserves extraordinary small lizards and geckos as inclusions, with their skins perfectly preserved, but unfortunately no snakes have been found in amber up to that date.

Which are your favourite specimens here?

The specimens preserved in alcohol are in very good shape despite the fact they were prepared in the sixties. The colourful specimens are quite attractive, although they were painted artificially.

What is your impression about Hungary and Budapest?

This is my first time in Hungary and I can say that I really enjoy being here. Both my experiences of working at the Collection of Herpetology and staying in the city have been a great pleasure.

Written by Bernadett Döme and Krisztián Kucska

Photos by Szabolcs Simó